Psychology experts believe that because the word “alcoholic” is always associated with rowdy, nomadic people, those who consume alcohol in more-than-usual amounts, believing that their drinking habits are still normal, tend to refrain from seeking help. Olivia Sorrel-Dejerine of BBC discusses this issue in detail.

Image Source: www.bbc.co.uk

Everybody thinks they know what an “alcoholic” is, but what about those who drink too much but fall short of the common definitions of alcoholism? Should there be a word that bridges the gap between alcoholic and non-alcoholic?

The term alcoholic – on its own to denote someone addicted to alcohol – was first used in 1852 in the Scottish Temperance Review.

Since then, millions of heavy drinkers have been confronted by friends and families with the stark question: “Are you an alcoholic?”

And millions have denied it. Rejected the label. Confessed only to maybe, possibly drinking too much. But utterly denied the A-word.

Alcoholics are people who fall asleep in skips. Alcoholics get into fights. Alcoholics start the day with a shot of whisky. Alcoholics are drunk all the time. Alcoholics can’t hold down jobs.

Image Source: www.bbc.co.uk

None of the above is necessarily true, but the intensely negative nature of the word alcoholic leaves some people scrabbling for an alternative.

“There is so much stigma,” says Kate, author of the blog The Sober Journalist. People are so frightened of it – their head fills with images of men drinking under bridges. “There is this huge number of people out there who don’t fit that stereotype but perhaps their drinking isn’t quite normal.”

Kate went to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings when she started to think she was drinking too much, about four or five years ago. “I felt I was out of place, I wasn’t alcoholic enough. I felt that everyone else had worse problems with drinking than I did,” she says.

There are other words for people who drink a lot. There is everything from the lightly derogatory “lush” to the more flowery “bibulous” to the prosaic “heavy drinker”.

But there is nothing as succinct as alcoholic. And some believe that this gap has an effect.

Professionals have started using other terms that would not be as negative as alcoholic because “many doctors feel that it is quite difficult to engage a patient if you talk to them about alcoholism”, says Dr Sarah Jarvis, a consultant for Patient.co.uk.

People have such vivid mental images of what it means to be an alcoholic that they measure themselves against that standard and do not seek help.

“They all have an idea of what an alcohol or problem drinker is but there is a different pattern for every drinker,” Jarvis says.

Not all experts share this view, however.

There’s a danger that avoiding the term “alcoholism” will only serve “to reassure people their drinking is OK when it isn’t”, says Moira Plant, emeritus professor of alcohol studies at the University of the West of England.

She agrees the widespread impression of the alcoholic as a vagrant or street-drinker prevents higher-functioning people with drink problems from seeking help. But she says the best way to tackle this is to correct false stereotypes, not downplay the situation faced by such individuals – many of whom are already in denial.

“People normalise heavy drinking,” she says. “They tend to overestimate what everyone else drinks. They say, ‘I don’t drink as much as my friends so it’s OK.'”

There have been other words to describe someone drinking too much. In the 19th Century “inebriate” was a popular term and the word “drunkard” goes all the way back to the 15th Century.

England’s Department of Health recommends that men should not regularly drink more than three to four units of alcohol a day and women should not regularly drink more than two to three units a day.

But drinking above these recommendations does not necessarily mean that the person is an alcoholic. It just means increased risk of health damage.

“An alcoholic is anyone who is dependent on alcohol and who is drinking to a level that will endanger their health,” Dr Jarvis says.

The term alcoholic is very much alive in the vocabulary of ordinary people, says Tim Leighton, director of professional education and research at Action on Addiction.

“In Europe and in the UK, there was a move away from the term in the 1960s; it was seen as derogatory. We now talk about ‘alcohol dependence’, but you don’t hear people in the street saying he is an ‘alcohol dependent,’ they say he is an ‘alcoholic,'” he says.

Dr Jarvis says it is a shame the words “hazardous” or “harmful” drinker aren’t used more widely.

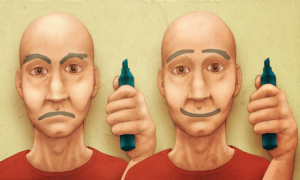

The issue with the use of the word “alcoholic” is that it is narrow. “You are either one or you are not,” Leighton says. “This is why some people prefer the term ‘alcohol dependence’. You can be an alcoholic without drinking too much – it is all about dependence, about losing control.”

For a long time, it was a strict category, there were specific criteria and if you fulfilled these criteria, you were an alcoholic, says Joseph Nowinski, one of the authors of the book Almost Alcoholic.

This is a stage for a lot of controversy – as long as you didn’t meet the alcoholic criteria, you would say, “I am not an alcoholic so I don’t have a drinking problem”, he says.

“There has never been a word for people who come to the point of asking themselves the question, ‘Do I have a problem or not?'”

Based on this, Nowinski and Robert Doyle came up with the concept of being an “almost alcoholic” to describe people who are not alcoholics but who “fall into a grey area of problem drinking”.

“The almost alcoholic zone is actually quite large. The people who occupy it are not alcoholics. Rather, they are men and women whose drinking habits range from barely qualifying as almost alcoholics to those whose drinking borders on abuse,” they wrote in the Atlantic.

“An expanded view of drinking behaviour in terms of a spectrum as opposed to discrete categories might be viewed by some as opening the door to over-diagnosing the associated problems. We believe the opposite will prove to be the case: that this paradigm shift will allow people to recognise problems earlier and to seek solutions without having to be labelled as alcoholics.”

“There is a huge range of alcohol problems,” Leighton says. “A lot of people with alcohol problems are not alcoholics.”

Until a new label is popularised there will be people who struggle to admit they have a problem, he says.

But for Kate, the existing term has come to make sense as her recovery has progressed.

“I feel that eight months ago I wouldn’t have said that I was an alcoholic and now I could say I am because I know what it means,” she says.

Dr. Sam Klein Von Reiche is a New Jersey-based psychologist specializing in treating addiction, including alcohol abuse. Learn more about her practice here.

![[A student demonstrating equipment at Colleen Carney's sleep lab at Ryerson University. Dr. Carney is the lead author of a new report about the effects of insomnia treatment on depression.] Image Source: nytimes.com](https://transcendingadversity.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/jp-sleep-popup.jpg?w=490&h=386)